Simon Grant

What is in the collection that you donated to the Hepworth Wakefield?

Barbara Hepworth

Installation view, The Hepworth Wakefield

Photo: Iwan Baan

Sophie Bowness

The Hepworth Family Gift comprises 44 surviving prototypes in plaster, aluminium and wood, as well as drawings, lithographs and screen prints. Barbara didn’t see the prototypes as works of art, but as the first stage in the process of casting a bronze or aluminium work. What is interesting about them is that these are the majority are the original plasters that she worked on with her own hands. You can see the marks of her tools on them. Texture was very important to her, and you get a good sense of this when you see them in the gallery. There is also a huge variety amongst the group, both in scale and texture.

Simon Grant

Were these prototypes small maquettes for larger works?

Sophie Bowness

Barbara didn’t make small works for larger projects. She always worked to scale, the only exceptions being the big commissions for which she was asked to provide a model. This is very different from Henry Moore, who would make a small maquette and have it blown up by his assistant. So, what Barbara called maquettes were usually made after the larger versions.

Simon Grant

We often think of Barbara Hepworth’s work as being predominantly white, but this wasn’t the case…

Barbara Hepworth

Installation View, Gallery 4: Hepworth at Work, The Hepworth, Wakefield

Sophie Bowness

No, I think people will be surprised to see that she produced works in many different colours. There were a number of reasons for this. Sometimes she coloured them to show up cracks or damage that might occur when the plasters were being delivered to the Morris Singer bronze foundry. She would cover them with a colour wash, so that those blemishes would show up. Other times it was done to indicate to the foundry the patina she wanted. For example, with Conversation with Magic Stones she wrote a note to say that the colouring she wanted was ‘a thin wash of brown, indicating very thin liver of salts and blue on the surfaces, that I want to be blueish-white’. There is also a group that she coloured up specifically for exhibitions, such as those that she exhibited in St Ives in 1968 when Barbara was given the Freedom of the borough of St Ives. And she exhibited one coloured plaster at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1962, as the bronze version was not ready.

Simon Grant

Do all her plaster prototypes survive?

Sophie Bowness

No, about one quarter has survived. The others would have been destroyed on her instructions, either by the foundry or, at times, when they were returned to her. It is somewhat chance what has survived, although she obviously kept the group that we have donated. She certainly wanted them kept, and to be shown. However, she didn’t leave any specific instructions for them, although there is a reference in a letter about leaving them to the right museum.

Simon Grant

How did she view this collection?

Barbara Hepworth

Installation View, Gallery 4: Hepworth at Work, The Hepworth, Wakefield

Sophie Bowness

It is difficult to know. She didn’t talk about them very much. We wanted to present them in order to give an insight into her working process. So, in the Hepworth Wakefield there is a room preceding the plasters gallery called Hepworth at Work. Here there is a section about her casting processes and her relationship with foundries, alongside a section on her monumental works in bronze and aluminium. The aesthetic qualities of the plasters are variable, there’s no question about it. Some of them are less finished; more show signs of the working process in them.

Simon Grant

One of the larger pieces on display is the prototype for Winged Figure 1961–2, the aluminium version of which is now seen by millions who walk past John Lewis on London’s Oxford Street. There is a nice story behind the genesis of this work.

Barbara Hepworth

Winged Figure

newly installed on the John Lewis building April 1963

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Sophie Bowness

Yes. In May 1961 Barbara was invited by John Lewis to design a sculpture for their headquarters. They asked her that the work ‘have some content that expresses the idea of common ownership and common interests in a partnership of thousand of workers’. The ethos of the firm greatly interested her.

Barbara Hepworth

The Hepworth Wakefield

Photo: Mark Heathcote © Bowness. Hepworth Estate.

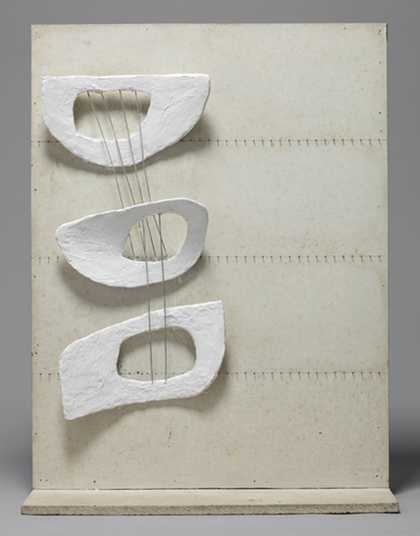

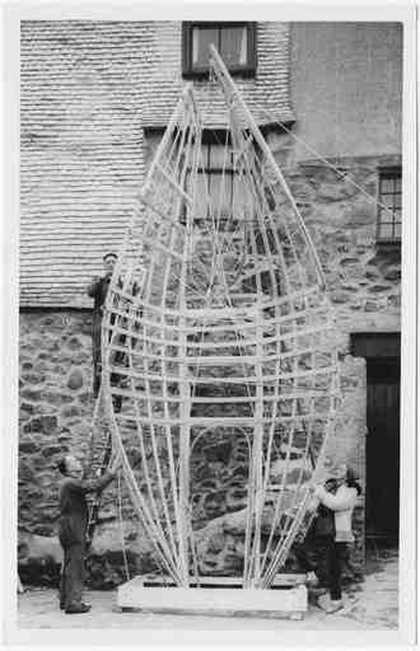

Her first proposal was, in fact, not what you see today, but a piece called Three Forms in Echelon. However John Lewis rejected this design as being insufficiently like a Hepworth. She then proposed an enlarged version of an existing sculpture Winged Figure I. This was accepted by John Lewis, and the prototype was made in St Ives in the yard of the Palais de Danse, initially in wood, and then in aluminium.

Barbara Hepworth

First stage of the armature of Winged Figure prototype in the Palais yard with Dicon Nance and Norman Stocker 1962

Photo: Mark Heathcote © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

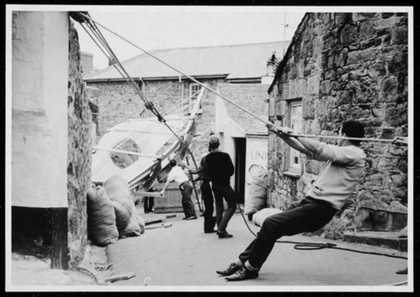

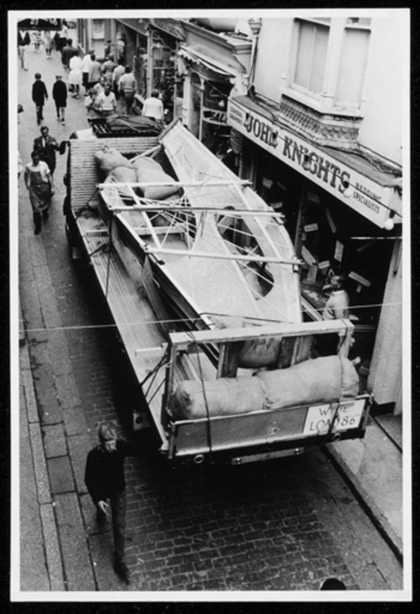

The surface was partially textured with Isopon, a polyester resin filler used in cars and boats, which gave it a very beautiful texture. In the summer of 1962, the sculpture made the journey through the small streets of St Ives and to the foundry in London – as you can see in the wonderful photographs that document this:

Barbara Hepworth

Winged Figure prototype leaving the Palais in St Ives to be cast August 1962

Photo: P.E.C Smith, St Ives © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Barbara Hepworth

Winged Figure prototype being transported along Fore Street on its departure from St Ives August 1962

© Bowness. Hepworth Estate

Simon Grant

How do you think she would have seen this collection if she were alive today?

Sophie Bowness

I think she always felt that she belonged to Yorkshire, although she didn’t actually return very frequently after the thirties. However it was clear that the Yorkshire landscape had a huge impact upon her .This came to the fore when she had moved to Cornwall. Here she found striking parallels with the Yorkshire landscape. There was the drama of the natural landscape as well as the contrast of the mining activities. Also, she often talked about the sculptural qualities of the rock. She was able to see a lot of the countryside as her father (a civil engineer) had a car, which was quite unusual in those days. Barbara talked a lot about the journeys through the landscape that they made in the course of his work. The idea of the added figure in the landscape was clearly derived from that early formative period. Seeing her sculptures in Wakefield means they have, in a way, come back to where she started.